Tech: “Are you sure you’re 9 weeks?”

Me: “Pretty sure, yes.”

Tech: “Is it possible your cycle was off, because it looks like closer to 4 weeks?”

My heart sank. It wasn’t possible. I had a positive at-home test 4 weeks ago. They can’t pick up the hormone until at least 3-4 weeks. There was a sac, but no embryo. The pregnancy wasn’t viable but my body continued to produce more pregnancy hormone as if everything was fine. I hadn’t miscarried on my own and it wasn’t likely I would. So, I was presented with three options: wait a while and see, take a pill to induce contractions and miscarry (likely painfully) at home, or undergo a D&C--surgical removal of the tissue. The D&C had the highest likelihood of success and the quickest recovery to when we’d be able to try again so I opted for that. I’d also be unconscious for the procedure so I thought it may be less emotionally scarring. I told my coworkers and students I would be out for a day for a “minor surgery,” “but don’t worry, nothing big, I’m fine!”

My spouse took the day off with me and took me to the hospital. The nurses were kind and the procedure went well. I wasn’t in much pain. I was told I may have residual bleeding for a few weeks. I did. I went back to work the next day.

After a few weeks, the bleeding seemed to stop for a couple of days and then started again. I assumed this was my period and thought nothing of it, but it continued for another couple of weeks. I called my doctor and by the time I was able to go in, I had been bleeding on and off for nearly two months.

Another ultrasound. More bloodwork.

There was some tissue left behind. Again, I was presented with three options: wait a while and see if the tissue passed on its own (unlikely since it hadn’t by now), take a pill to induce contractions and hope the tissue dislodges (unlikely again), or undergo another D&C--this time with a camera. I opted first for the pill this time. I had maxed out my deductible and out-of-pocket copay with the first D&C in November ($6000) and it was now January so I would be looking at another similar bill should I have to have surgery. The pill caused a lot of cramping and some bleeding, but alas, some tissue still held on. At this point, leaving the tissue would prevent me from being able to get pregnant and could eventually pose an infection risk. So, another surgery.

I told my coworkers and students that I was going in for a followup surgery to the first, but again, “don’t worry, nothing big, I’m fine!” This time the procedure didn’t go as well. I had to stay in the hospital for several hours afterward due to an irregular heart rhythm. I was in a lot more pain this time due to how aggressively they had to scrape my uterus. I had now indebted myself to the hospital for nearly $12k and gone through physical and emotional turmoil with nothing to show for it. I returned to work the next day.

Miraculously, we were able to get pregnant again shortly after the second procedure, but unlike the first time, my first reaction wasn’t excitement. More than anything, I was scared. I was scared to become attached. I was scared to potentially go through all of that again. When we go to doctor’s appointments and ultrasounds now, and hear the heartbeat, or see her move, the biggest feeling I have is relief. Every time I feel a pain in my stomach, a part of me panics. Nobody tells you that the baby moving can actually be painful.

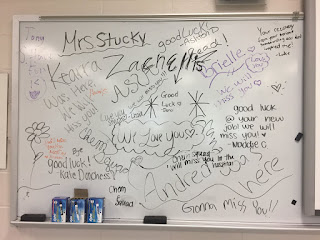

In going through this, I’ve learned how common pregnancy losses truly are. I’ve recently become more open about my experience and have shared with my coworkers and even some students (who had put two and two together with the "surgeries" and my new pregnancy and had asked if they were related). Many people have come to me to share similar stories. At the end of the school year, I told my students and coworkers I was pregnant and while I was happy to share that, I was also deeply concerned that I could come back in the fall and not be pregnant anymore.

I am trying to stay positive and enjoy this pregnancy rather than to be paralyzed by fear, and I think sharing what I’m going through has helped. Reading other women's stories helped me tremendously and I hope my story can help others too.